Updated January 29, 2023 at 5:09 PM ET

Ford Kuramoto was only 3 years old when his family had to leave their Los Angeles home to be taken to the Manzanar internment camp in the California desert. Frances Kuramoto, Ford's wife, was born in the Gila River camp in Arizona.

They are among the more than 125,000 Japanese Americans interned during World War II who are now being recognized in the Ireichō, or the Sacred Book of Names.

A yearlong exhibit at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, the Ireichō project provides a physical context to the number of Japanese Americans' lives forever changed by the actions of their own government.

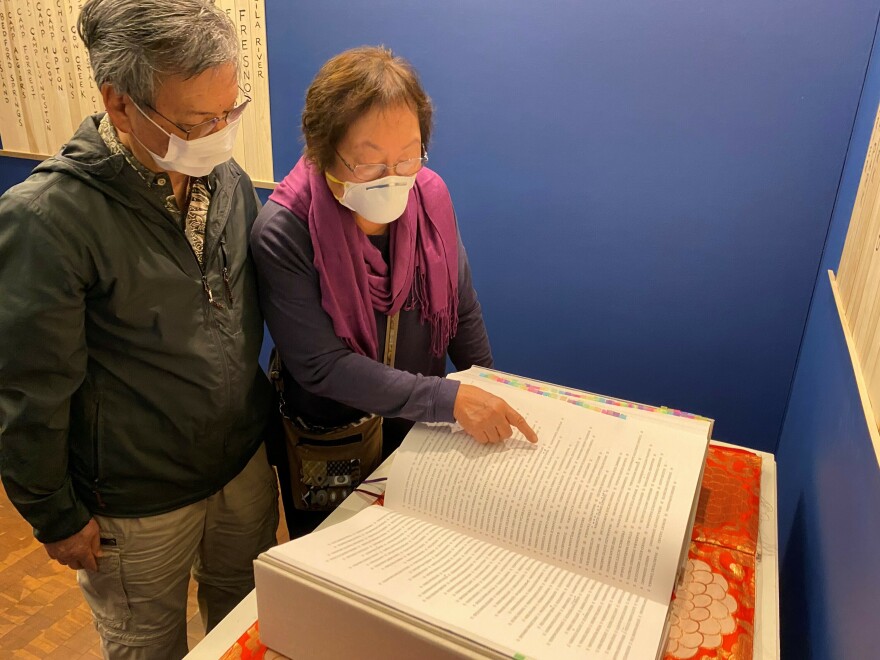

The book, kept under glass, features the names laid out across hundreds of pages.

On a visit to the museum in January, Frances Kuramoto said she was moved by the sheer size of the Gutenberg Bible sized book, sharing the names of those held without the conviction of a crime or the ability to appeal. "You span through all those names and you think: Oh my god, all those people were there. Incarcerated," she said.

The museum encourages those who were incarcerated, their families, and other visitors to stamp names in the book as a way to counter the erasure of identities.

Frances and Ford Kuramoto are among the few remaining interned Americans who can still leave a mark under their own names.

The Ireichō is the centerpiece of the exhibit. It's surrounded on the walls by pieces of wood listing the 10 U.S. internment camps and dozens of other relocation areas around the country. A small glass vial is attached to each piece, containing topsoil from that location.

A tile embedded in the cover of the Ireichō is made from soil from 75 sites.

"It brings back memories of being a toddler at Manzanar," says Ford, who has clear memories of his time in the harsh conditions of the internment camp. Over the course of its operation from March 1942 to November 1945, 11,070 people were processed through Manzanar; some were held for as long as three and a half years.

"I could wander around all I wanted to, but there's basically nowhere to go," he says. "It was just barracks, barbed wire fences, and the military guards with guns up in the towers. That was, that was life."

The book aims to keep memories alive

Growing up, their incarceration during World War II was not a topic of conversation in Ford and Frances' families. "I grew up not ever knowing what was really going on or what happened, because my parents never, ever, ever talked about it," says Frances.

The couple, both in their 80s, say they are becoming somewhat forgetful when it comes to all the accounting of internment. As the last of an interned generation, the Kuramotos are hoping the next generation will carry forward the memories they can still recall.

After seeing her name in the book with so many others, Frances says the exhibit is a conduit for sharing the details of life at the time. "This Ireichō and the sharing of family histories and stories is really, really important to pass it on to our children and to anyone else who will listen."

The Kuramotos are accompanied at the exhibit by their siblings, extended family, and their son Jack.

"It's sort of like passing the torch to another generation," Jack Kuramoto says.

"Also it's part of passing the heritage along."

The youngest members of the family in attendance are the Kuramotos' nieces.

"I feel honored to be here and represent our family," says Dawn Onishi, the older of the two nieces, as she places a seal under the first letter of her grandfather's name. "And I'm honored to have been able to be here to stamp the book."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.